![]()

Breaking News & then some—>

Barbwire

and Nevada Press Assn. Hall of Famer

Guy Louis Rocha on PBS-Reno "House

with a History"

Livestream Sunday 9-15-2024 5:30 p.m. PDT KNPB TV-5/Northern Nevada

https://www.pbsreno.org/livestream/

Rocha inducted to Nevada Press Assn. Hall of Fame in Reno on Saturday

9/14/2024

2

more Barbano nominees elected to Nevada Press Association Hall

of Fame

Prof

. Jake Highton and Guy Louis Rocha win

Carson City Nevada Appeal / 8-15-2024

2024:

4 Barbwire nominees honored, 4 to go

2025:

5 down 3 to go

We

need truth-tellers like Guy Rocha now more than ever

By

Jon Ralston / Nevada Independent 9-28-2025

‘Facts

over folklore’: Guy Rocha, Nevada’s ‘myth buster’ historian, is dead at

73

By Frank X. Mullen / Reno News & Review 9-25-2025

Guy

Louis Rocha, 73, dies one year after hall of fame induction

Guy Louis Rocha

'Never knew a stranger'

By Siobhan McAndrew and Jason Hidalgo / Reno Gazette-Journal

9-19-2025

![]()

THE MANY IMAGES OF THE COMSTOCK MINERS' UNIONS

by

Guy

Louis Rocha

|

|

There are three Miners' Unions, one at Virginia City, one at Gold Hill, and the third at Silver City ... [T]hus far, the principal officers and leading spirits of the several organizations have been men of such honesty of purpose and have shown such fairness in all of their demands that there has been no trouble between miners and mine owners.

-Dan DeQuille, The Big Bonanza, 1876

The miners' unions on the Comstock Lode are unworthy champions of the labor cause, for they substitute might for right, and place personal interest in the room of justice. There is no question here of self-preservation, but rather of self-aggrandizement, and it is a disgrace to the Washoe district that such despotism should have existed within its limits for fourteen years without one effective revolt.

-Eliot Lord, Comstock Mining and Miners, 1883

The organizations by which the Comstock miners have maintained wages, have ruled in this respect under all administrations, and still continue to rule, are simply "Unions." At Virginia City, Gold Hill, and Silver City their word long ago became law.

-Charles Howard Shinn, The Story of the Mine, 1896

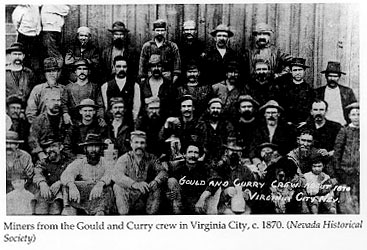

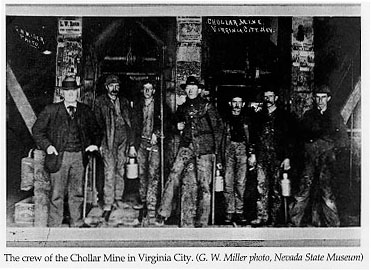

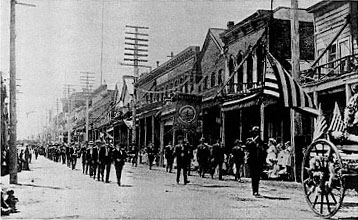

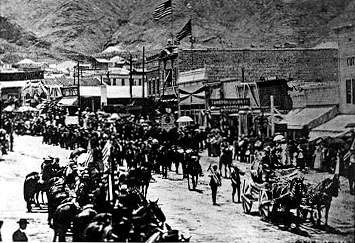

The first miners' unions of the American West were those organized on the Comstock. Four years after the 1859 discovery of the great gold and silver quartz lodes at Gold Hill and Six-Mile Canyon, underground miners attempted to unionize. During the formative period of unionization in and around the mines, disputes between corporate capital and organized labor soon led to confrontations, particularly over the four-dollar-a-day wage and closed-shop issues. Blacklisting by the mining companies and a show of military force, directed by Nevada Territorial Governor James W. Nye against the Storey County Miners' League during the mining depression of 1864, inaugurated a "heritage of conflict" in the western hardrock-mining industry that continued well into the twentieth century.

|

|

While militant in their tactics, the unions of Virginia

City, Gold Hill, and Silver City accepted the basic tenets of a capitalistic,

industrial economy. The union miners discovered, following their initial

setbacks, that the means to power in a locality dominated by one industry

was to influence or control essential elements of local government through

the ballot and volunteerism — especially in law enforcement, fire protection,

and the militia. Beginning in 1868, and for more than a decade, the Storey

County sheriff was either a present or past president of the Gold Hill

or Virginia City miners' union. Most of the police chiefs of the three

Comstock municipalities were either union miners or men who relied upon

union support to get elected. The first president of the Storey County

Miners' League, William Woodburn, was elected district attorney in 1870.

The unions also influenced legislation affecting their interests by electing

miners and other partisans to the state legislature and the United States

Congress. Woodburn, a member of the Virginia City union, was elected to

Congress in 1874 and again in 1884 and 1886. In 1870, James Phelan, Virginia

City union president, won a seat in the state Senate, and Angus Hay and

George W. Rogers, both of the Gold Hill union, were elected to the state

Assembly. Many other union miners were elected to the state legislature

in succeeding years. Although union officers were required to resign their

positions if elected to public office, it is evident that these men's

allegiance remained with their unions.1

Ultimately, the miners' unions succeeded in wresting basic concessions

involving wages, working conditions, and union security from the absentee-owned

mining corporations because they were able to maintain community support

during times of dispute and negotiation. The business sector, especially,

was heavily dependent upon the income of the miners who bought the merchants'

products and services. A strike could paralyze commerce, and flood the

deep mines by stopping the pumps, exciting the stock market into a selling

frenzy. In addition, both the communities and the mining corporations

had become reliant on union miners for their fire and militia protection.

Absorbing the lessons from their earlier confrontations with mine owners,

the unions now pursued coercive tactics directed at management. For example,

in negotiating a minimum wage for underground miners in February 1867,

a Gold Hill union official none too subtly assured the president of the

Imperial Mine that "the Military Co's, Fire Co.'s, etc. of Gold Hill

and vicinity were ever ready to protect the property and officials of

mines paying $4.00 per day." Despite the underlying industrial tension,

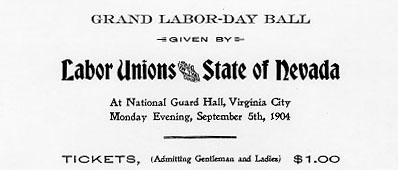

the miners and their unions were an integral part of Comstock social and

civic life, sponsoring or supporting numerous public events, the only

public library, and a private hospital — Saint Mary's — in Virginia

City.2

The efforts of organized mining labor in perfecting their unions on the Comstock by the early 1870s established the general pattern of union organization and labor-management relations throughout the mining West for the next two decades. Comstock miners, in search of new bonanzas and job opportunities, exported their union principles to such camps as Bodie, California; Deadwood, Dakota Territory; Leadville, Colorado; Tombstone, Arizona Territory; and Butte, Montana Territory. Almost without exception the new unions adopted the constitution and bylaws of either the Virginia City or the Gold Hill miners' union and with little more revision than altering the meeting day or raising the sick benefit. Few miners' unions, however, enjoyed the sustained level of success achieved by those on the Comstock.3

Beginning in the early 1880s, the focus

of union activity in the western mining industry shifted elsewhere

as the Comstock rapidly declined and a general mining depression

settled on Nevada. No longer the Gibraltar of unionism, the Comstock

labor organizations, while still a viable force in Storey and

Lyon counties and in state politics, found themselves on the

fringe of the mining union movement. No representative from the

Comstock unions attended the organizational meeting of the Western

Federation of Miners (WFM) in Butte, Montana — the new Gibraltar

— in 1893. In fact, the three local unions did not join the

regional federation until 1896, and they maintained an on-again,

off-again affiliation until their demise in the 1920s. The remaining

union miners and mining companies on the Comstock made hard concessions

on both sides in coping with a faltering local industry in the

1880s and 1890s. The four-dollar-a-day wage survived, but at

the expense of lengthening the work day to ten hours in the upper

levels of the mines.4

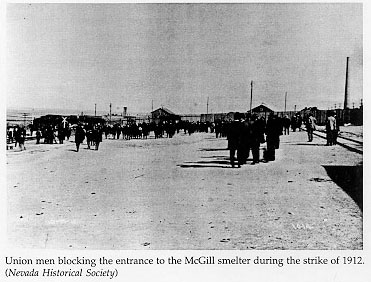

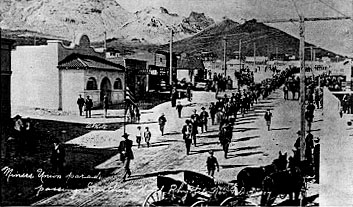

With the mineral discoveries at Tonopah, Goldfield,

Ely, and elsewhere in the state, mining in Nevada sustained a

tremendous upsurge after 1900, and brought some new investment

and prosperity to the Comstock and its miners' unions. Nonetheless,

the controversial and sometimes violent activities associated

with Rhyolite, Ely-McGill, the socialist-oriented WFM locals

in Tonopah, Goldfield, and Manhattan overshadowed the brief resurgence

of the Comstock unions. There was a vivid contrast between the

socialism of the WFM and its anarchosyndicalist ally the Industrial

Workers of the World (IWW) (founded in Chicago in 1905) and the

more traditional industrial unionism of the Comstock miners'

unions. Viewing this, Nevadans seemingly forgave if not forgot

the militancy of the Comstock unions and longed for the apocryphal

golden age of mining labor-management relations that they perceived

had once existed in Storey County. Commemorating the fiftieth

anniversary of the Virginia City Miners' Union in 1917, former

Storey County district attorney and district judge Charles E.

Mack, himself a member of the union for forty years, claimed

that the "conservatism displayed by the miners' unions of

Virginia, Gold Hill and Silver City ... which should govern all

labor unions... won the confidence and respect of everyone."

Governor Emmet Boyle, who was a native of Gold Hill, graduate

of the University of Nevada, and a mining engineer by profession,

heartily concurred with Judge Mack in making the closing remarks

at the celebration.5

The records and other primary accounts of the Comstock miners' unions, however, clearly show that the statements by Mack and Boyle extolling the cordial relationship between management and organized labor were exaggerated and nostalgic. Just the same, the image of the Comstock miner and his unions has been characterized alternately as harmonious and uncontentious, and as despotic and militant, in popular and scholarly works over the last one hundred and twenty years. A review and analysis of the historiography helps to explain the sources and evolution of the disparate images of the Comstock miner and his unions.

While federal troops began occupying southern cities in 1864 at the close of the Civil War, they also marched into a western mining town in a show of force against a newly organized miners' union. Nevada Territorial Governor James Warren Nye, a Lincoln appointee, former New York City police commissioner, and ardent supporter of the North, was opposed to any effort by the Storey County Miners' League to enforce its public notice of September 19 which, in effect, demanded a closed shop in all the Comstock mines after September 27. This union action followed in the wake of an unsuccessful attempt on the part of the mine owners to lower unilaterally the minimum underground wage by fifty cents, to three dollars and fifty cents per hour. Governor Nye, a mine owner himself, hastily dispatched a telegram to the commander of Fort Churchill, Major Charles McDermit, requesting that two heavily armed companies of cavalry be immediately sent to Virginia City. As his communication of Saturday, September 24, forcefully conveyed, Governor Nye was willing to confront the Storey County Miners' League with armed force, and to shoot its members if necessary, in his effort to preserve the peace:

Sir: I am quite apprehensive of trouble with the Miners' League on Tuesday next — perhaps before. They have assumed a belligerent attitude, and have undertaken to coerce the employers into their measures. It must not, it shall not, be done. When this came to my knowledge I telegramed (sic) to General McDowell [commander, Department of the Pacific] to countermand the order for removal of the troops from the fort; hence the order. I have been here from Carson two days, and am fully impressed with the belief that the peace of the Territory depends upon the presence of two companies of cavalry from Sunday evening till Tuesday. I hope you will send them, with plenty of ammunition. Do so, and oblige.6

This show of force in late September, and another in early October, substantially contributed to the demise of the Storey County Miners' League. Although no violent clashes occurred between the cavalry companies and league members, primarily because the union had retracted its demand for a closed shop four days prior to the first arrival of troops, the union miners had learned a harsh lesson in labor-management relations. This lesson — that "might is right" — did not go unheeded as the miners of the Comstock organized new and successful unions after the 1864-65 depression in Gold Hill (1866), Virginia City (1867), Silver City (1874), and throughout the mining West in the late nineteenth century.7

Governor Nye's call for troops may be the first use of the military to suppress activities of a labor union in the trans-Mississippi West. Still, many historians and other writers have characterized labor-management relations on the Comstock as having been much more cordial and peaceful than they actually were. Until Richard Lingenfelter's The Hardrock Miners: A History of the Mining Labor Movement in the American West, 1863-1893 was published in 1974, no systematic study had been conducted that closely scrutinized the evolution of organized mining labor on the Comstock. Lingenfelter extended the "heritage of conflict" theme (first introduced in 1950 by Vernon Jensen in his seminal work on the Western Federation of Miners) back to the initial attempts at organizing miners' unions in the American West. Interestingly enough, Lingenfelter overlooked the confrontation between the Storey County Miners' League and the military, and thus the implications of such drastic action on the future of labor-management relations in the region's developing nonferrous metals industry.8

|

|

William Wright's popular History of the Big Bonanza (1876) is the principal source for the mythical image of the contented miner and benevolent mining corporation. This first book-length history of the Comstock, with its many entertaining anecdotes and promotional hype, projected an unqualified positive image of relations between corporate capital and the miners' unions. Wright — or Dan DeQuille, under which nom de plume the Virginia City journalist achieved renown — made no mention of the labor troubles surrounding the Storey County Miners' League in 1864. Referring to the three Comstock miners' unions in 1875, DeQuille wrote that "thus far, the principal officers and leading spirits of the several organizations have been men of such honesty of purpose and have shown such fairness in all of their demands that there has been no trouble between miners and mine owners.9

The History of Nevada (1881), edited by Myron Angel, helped to dispel the myth of tranquil labor-management relations on the Comstock. As a "mug" or subscription history, it devoted brief space — less than one page — to the development of the Comstock miners' unions. Angel's staff was writing at the time of the Leadville miners' strike in Colorado, which involved the calling out of the state militia by the governor and occurred during a period marked by ugly anti-Chinese demonstrations in the West, inspired by organized labor. These events may explain the article's ambivalence regarding the nature and purpose of the unions. The unions "were on generally good terms with their employers, and in some instances the organizations were approved by [the employers] as giving the mining population a head with which to communicate," it noted, "whether beneficial or not is a question that remains undecided. Like all organizations for especial purposes they are liable to abuse their strength and become in turn the tyrant." By way of illustration, two examples were provided of how the Comstock unions, during the mining depressions in August 1864 and February 1877, garnered concessions from the mining superintendents, not through the use of violence, but rather by exercising a liberal measure of "forcible persuasion."10

Eliot Lord, in his landmark study Comstock Mining and Miners (1883), protested vehemently against what he labeled the "despotism" of the miners' unions. "The miners' unions on the Comstock Lode," Lord wrote in 1883, "are unworthy champions of the labor cause, for they substitute might for right, and place personal interest in the room of justice. There is no question here of self-preservation, but rather of self-aggrandizement, and it is a disgrace to the Washoe district that such despotism should have existed within its limits for fourteen years without one effective revolt." Writing a history of the Comstock at the request of the United States Geological Survey, Lord challenged the image of amicable labor-management relations. He blasted the absentee mine owners for their inefficient operations and blatant stock-jobbing, but, more important, he roundly condemned any organization that would challenge a fundamental principle of laissez-faire economics and establish an arbitrary minimum wage. Although critical of both the miners' unions and the corporations, Lord singled out the labor organizations as the prime culprits responsible for the Comstock's deepening depression in the early 1880s. The unions' uncompromising position on the four-dollar-a-day minimum wage was leading the once-great "Washoe District" to ruin; he argued that the "partisan guild [who] fix their own wages, brow beat their employers, and exclude other laborers [notably the Chinese] from the district which they control had far too long overstepped their bounds."11

Lord's critical and biting analysis of labor-management relations on the Comstock was unquestionably the most thorough treatment of the topic until the publication of Lingenfelter's The Hardrock Miners some ninety years later. Still, despite the fact that most historians of the Comstock generally borrowed liberally from Comstock Mining and Miners, they apparently glossed over Lord's harsh criticism of the unions in the chapters entitled "Industrial Conflicts" and "The Laborers of Washoe." With the exception of Hubert Howe Bancroft's work Popular Tribunals (1887), each successive study of the Comstock portrayed the miners' unions in their relations with the owners in a generally positive light, either ignoring the early years of open conflict or attributing little lasting significance to the rocky beginnings of organized mining labor. The histories primarily focused on the unions' most successful years in the late 1860s and 1870s, and emphasized the seemingly peaceful relations between miners and owners without critically examining the delicate balance of power in those years which, on a number of occasions, teetered on the brink of violence.

Hubert Bancroft, writing during the period of the sensational Haymarket bombing and trial in Chicago, considered the Storey County Miners' League a vigilante organization of the lowest order, "which was not always temperate in its counsel nor beneficial to society in its operations." In comparing the Miners' League to vigilante groups, he wrote,

there is a vast difference in the association of the best elements of a community, actuated by no personal ambition and possessing no political aspirations, banding [together] for the support of social morality and good order, for the upholding of law and government in so far as law and government can sustain themselves, but never harboring designs of their overthrow — there is a vast difference I say, between such organizations and the leagues of disaffected laborers, secret political societies, and the coalescing of lawless desperation.

Of considerable importance is the fact

that Bancroft justified his caustic assessment of the Miners'

League by citing a letter from Governor Nye to John P. Usher,

United States secretary of the interior, explaining why he was

late in making his report as Nevada superintendent for Indian

affairs. The correspondence, dated September 25, 1864, informed

the secretary that "for the last five weeks this territory

has been in considerable turmoil and commotion, owing to the

apprehended raids from avowed disloyalists from California and

this territory on the one hand, and the riotous and unlawful

proceedings of persons composing what is here called the Miners'

League on the other." Nye went on to report that "on

two occasions I found it necessary to order out the military

from Fort Churchill to the towns of Virginia and Carson to be

in readiness to suppress or prevent these anticipated disorders."

Ironically, Bancroft appears to have been the only historian

aware of Nye's use of the military to suppress the Miners' League.

He made no further reference to the "disreputable"

Comstock miners' unions in Popular Tribunals.12

Bancroft's History of Nevada, Colorado,

and Wyoming (1890) devoted three pages of text to the activities

of organized mining labor on the Comstock, erroneously claiming

that the Miners' Protective Association, organized in 1863, survived

to form the basis for the Storey County Miners' League in the

following year. The tone of the section is considerably less

harsh than the treatment in Popular Tribunals. No

mention is made of Nye's call for troops to the Comstock or of

vigilante groups composed of "disaffected laborers."

|

|

The reason is not altogether obvious. Bancroft's assistant, Frances Fuller Victor, writing on her employer's behalf, composed most of the Nevada section of the historical volume. John Walton Caughey's biography of Bancroft pointed out that the acclaimed historian of the West did not write many of the books of history that were published under his name, although Popular Tribunals was one of the publications that he actually wrote himself. In Bancroft and Fuller's History of Nevada, Fuller wrote that the Miners' League failed because it was undermined by nonunion members who "covertly" accepted the mine owners' lower wage, thus "crowding out the four-dollar men, who finally withdrew from some of their least tenable positions, and the league was finally dissolved." Despite the fact that only one sentence and a footnote were devoted to activities of the Comstock unions organized after 1865, the message was clear that after the Storey County Miners' League fiasco the new labor organizations maintained the upper hand in labor-management relations. As Fuller wrote in the late 1880s, "the mine-owners had never been able to establish a uniform price lower than $4, while the miners formed 'unions' to maintain the rate, in which effort they were never defeated." 13

In writing his history The Story of the Mine, as Illustrated by the Great Comstock Lode of Nevada (1896), Charles Howard Shinn apparently did not consult Bancroft's works, but he did rely heavily on History of the Big Bonanza and Comstock Mining and Miners. In fact, Shinn called Dan DeQuille "the only real historian of the Comstock," which helps explain why he projected an overall positive image of labor-management relations in the mining industry. Lord's influence on Shinn's study cannot be downplayed either. While Shinn applauded "the remarkable efficiency of the well-fed, well-clothed, and contented miners of the Comstock," he also graphically pointed out that "there was never any united effort to reduce wages, so violent and immediate the revolt against the slightest move in that direction, so strongly were the unions supported by the whole community. ... The Unions held an impregnable fortress." Despite Shinn's hyperbole, he seemed well aware that labor peace on the Comstock depended on a delicate balance of power between the militant labor unions, with their sizeable community backing, and the absentee-owned mining corporations. 14

Three publications — Carl B. Glasscock's The Big Bonanza: The Story of The Comstock Lode (1931), George D. Lyman's The Saga of the Comstock Lode (1934), and Grant H. Smith's The History of the Comstock Lode, 1850-1920 (1943)-made only passing reference to the relations between owners and unions. Glasscock, citing DeQuille, Angel, Lord, and Shinn in his bibliography, wrote just one sentence relating to collective action on the part of the Comstock miners - a mention of the victorious strike against the mine owners' fifty-cent wage reduction in the summer of 1864. Writing this historical potboiler shortly after the New York stock market crash of 1929, Glasscock was preoccupied with criticizing the mine owners, including the venerated John W. Mackay, for the effect that their stock manipulations had had upon the Comstock economy.15

Lyman's popular history was concerned only with affairs on the Comstock up to and including 1865. No mention is made of the Miners' Protective Association, and a chapter devoted to the Storey County Miners' League centered more on describing the rowdy demonstrations against the 1864 fifty-cent wage reduction than on analysis of this labor-management confrontation and those that followed over the next three months. Much of his documentation for the volatile period depended on the Reminiscences of Senator William M. Stewart (1908). The autobiography of this successful Comstock corporate-mining lawyer and long-time United States senator for Nevada, written late in his life, is a questionable source of information given Stewart's penchant for exaggerating his role in historical events. After accepting Stewart's version of the episode, in which he credited himself with personally negotiating a wage settlement, Lyman concluded his chapter entitled "Borrasca" with the formation of the Miners' League and a procession of union miners passing beneath the balcony of the International Hotel in Virginia City; there, "Bill Stewart might have been seen to lean far over the railing, wave his hat, and shout — 'Three cheers for the honest miner!' " He never returned to the tale, which effectively culminated in the elimination of the Storey County Miners' League from the Comstock with the assistance of Territorial Governor James Nye.16

Grant Smith, who spent much of his youth on the Comstock and later worked for a number of the area's mining corporations as their attorney in San Francisco, devoted the majority of his study to the mining entrepreneurs and companies that developed the mining district's mineral resources and manipulated the stock market. The book, dedicated to John Mackay, the revered "Bonanza King," was the first work to assess critically the borrasca years on the Comstock after 1880. His brief discussion of the underground miners totaled less than three pages out of some three hundred. While the treatment is sympathetic, Smith calling the miners "the lords of labor" and "men among men," most of the narrative is dependent on Lord and Shinn as sources, with only passing reference made to the miners' unions and their activities. In mentioning concessions won by the unions, he stressed that generally "there was no violence or any destruction of property."

|

|

It is interesting that Smith, born in 1865 at Sutter Creek, California, briefly worked in the Virginia City mines in his early teens before the family moved to Bodie in 1879. He recalled that there was no ceremony or initiation associated with joining the union. Still, he was too young to have known much personally about the early history of organized labor in the mines. The fact that his father was a professional gambler and not a miner also helps to explain why Smith relied very little on family reminiscences in writing about the miners and their unions.17

With the publication of Heritage of Conflict: Labor Relations in the Nonferrous Metals Industry up to 1930 (1950), Vernon Jensen, professor of industrial and labor relations at Cornell University, offered an interpretation of labor-management relations in the metal-mining industry that was based upon the assumption that the Comstock era (1859-80) did not contain elements of "belligerence and conflict" between labor and capital in the mines. For Jensen, the roots of the heritage of conflict that continuously plagued the history of the WFM, established in 1893, were to be found in Colorado Governor Frederick W. Pitkin's call for troops and declaration of martial law following an 1880 miners' strike for increased wages and the eight-hour day. Seemingly unaware of earlier confrontations on Nevada's Comstock Lode, Jensen argued that the events surrounding the Leadville strike would "build up animosities which were to add up to a heritage bequeathed unwittingly to the future."

Jensen's analysis of the Miners' Protective Association, the Storey County Miners' League, and the subsequent successful Comstock miners' unions, while dependent on Eliot Lord's work as a source, does not embrace Lord's sharp criticism of the unions for their "despotism." Instead, citing Grant Smith, Jensen claimed that the Virginia City Miners' Union, and presumably the other successful Comstock miners' unions, "were long a model of vigorous, constructive unionism [and] had a remarkably peaceful life.' 18

Jensen's sympathetic treatment of the Comstock miners' unions reflected his support for the "constructive" industrial unionism practiced by the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (UMMSW) - after 1916 the successor of the WFM - during the pro-labor years of the Franklin Roosevelt administration. The heritage of conflict in the metal-mining industry of the American West, he argued, had for many years deflected the WFM from the more conservative brand of business unionism practiced by the Comstock unions, forcing it onto a radical path associated, at times, with socialism, anarcho-syndicalism, and the overthrow of the capitalist system. Although the WFM finally abandoned its radical agenda in 1911 when it reaffiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), it took many years for the stigma of the past associations to diminish. "The only basis for good labor relations is humane living, mutual respect, and business-like behavior," Jensen wrote in the final paragraph of his book. "It takes all three in combination to produce the basis upon which to build wholesome labor relations." Jensen presumed that these three essential elements were an inherent part of the collective bargaining process on the Comstock. He failed to discover that the origin of the heritage of conflict in the western metal-mining industry was to be found in Storey County, Nevada Territory, and predated the Leadville, Colorado, strike by sixteen years.19

In Mining Frontiers of the Far West, 1848-1880 (1963), Rodman Paul synthesized the best of DeQuille, Angel, and Lord in assessing the interaction of organized labor and mining capital on the Comstock. Although he relied almost entirely on secondary sources, Paul presented the most balanced analysis of the subject up to the time of his writing. He was mistaken when he stated that the Miners' Protective Association "was expanded into a 'Miners' League of Storey County' a year later." In all likelihood, Myron Angel's History of Nevada was the likely origin of the error. In contrast to this, Paul's conclusion that the Miners' League had disintegrated by 1865 "under the twin pressures of blacklisting and of the hard times that so adversely affected employment in 1864-1865" was a reasonable one given his sources. Bancroft's Popular Tribunals provided the additional evidence of governmental coercion though the use of the military, which, in effect, had allowed the mine owners to pursue their anti-union objectives during the Comstock's first sustained economic depression, in the midst of the Civil War.

|

|

Paul was also in error when he stated that the first successful Comstock

miners' union was the Virginia City Miners' Union, organized on July 4,

1867; in fact, the Gold Hill Miners' Union had been created some seven

months earlier, on December 8,1866. Nonetheless, he openly addressed the

issue of coercion as a tactic adopted by the union miners to obtain their

demands. Paul, in implying that force, or its threat, was an element in

labor-management relations, cited a convincing illustration that occurred

shortly after the formation of the Virginia City Miners' Union, when a

"'committee' of 300 muscular Miners, 'persuaded' the recalcitrant

owners to yield" to a demand of four dollars a day for all underground

work. He further pointed out that in 1869 the "competition from Chinese

labor was so vigorously opposed" by the two Comstock unions "that

there was no further consideration of it." Paul demonstrated that

the miners' right to collective bargaining had not been won on the basis

of mutual respect between employer and employee but rather after confrontation

and coercion on both sides."20

In addition to Paul's landmark study, the year 1963 saw publication of a similar survey work, William S. Greever's The Bonanza West: The Story of the Western Mining Rushes, 1848-1900. Greever, in his chapter entitled "Life in the Nevada Mines," introduced the reader to the average Comstock miner, but said next to nothing about his unions. Drawing upon the works of DeQuille, Lord, and Smith, he described the stature, age, weight, diet, clothing, and housing of the typical underground miner, as well as the dangerous working conditions he encountered in the mines. Just one paragraph in the book dealt specifically with the miners' unions on the Comstock, and it made reference only to the four-dollar minimum wage being established by 1867, compulsory union membership, and the provision of sick and death benefits by the labor organizations.21

Russell R. Elliott provided a short, serviceable overview of the Comstock unions in his college text History of Nevada, first published in 1973. Focusing on the labor activity in the 1860s and 1870s, Elliott seems to have relied primarily on DeQuille, Lord, and Paul for source material. He avoided the common error of linking the Miners' Protective Association directly with the founding of the Storey County Miners' League, but, like Rodman Paul, incorrectly claimed in his first edition that "the miners at Virginia City were the first to form a successful labor organization."

In analyzing the events surrounding the demise of the Miners' League, Elliott suggested that the setback for mining unionism on the Comstock was "apparently more the result of hard times than any antilabor sentiment among the owners." He apparently downplayed Lord and Paul's references to the owners' surreptitious blacklisting of league members beginning shortly after the union's creation, and he was obviously unaware of Governor Nye's call for troops as recounted in Bancroft's Popular Tribunals. Instead, he argued for a cooperative relationship between the unions and the mining companies, much like Vernon Jensen:

The achievements of the Virginia City and Gold Hill Miners' unions in maintaining wages and controlling the camp without a major labor strike are rather outstanding when one remembers that labor organizations were just getting a foothold on the national level at this time. In trying to explain this success one must consider the richness of the ore, the difficulty of obtaining skilled miners, the need for a stable working force (which high wages guaranteed) to exploit the mines properly, the high living costs when the $4 wage was first introduced, and the moderation of the miners in their demands. Then, too, it seems apparent that both operators and miners took pride in the fact that the Comstock was the model for western mining. It was the richest mineral area in the United States and it contained the best machinery and the best engineers - why not the best and highest paid miners? The operators saw another advantage of a strong union membership; the union, with some company help, cared for the sick and disabled miners and helped to take care of the family of any miners who met death by accident."22

This historiographical overview forms a background for consideration of the most authoritative work on Comstock labor-management relations to date, The Hardrock Miners, published in 1974. Richard Lingenfelter, a scientist by vocation and an accomplished historian by avocation, utilized both primary and secondary sources to document the activities of hardrock miners' unions in the American West between 1863 and 1893. Nearly half the book is devoted to activities of the Nevada unions established in Gold Hill, Virginia City, and Silver City, and Lingenfelter has offered considerable evidence of the use of armed force and coercion by both mining companies and organized labor in their industrial relations. In addition, he alluded to the union miners' influence in the local militia units, fire companies, and law enforcement agencies as an example of how the labor organizations recognized that their survival depended upon controlling or influencing key elements of local government - something the miners had failed to realize, or realized too late, when they organized as the Storey County Miners' League. 23

|

|

Lingenfelter forcefully conveyed that labor-management relations in the Comstock's mining industry, and throughout the mining West, were characteristically adversarial in nature. His treatment of the 1871 Amador War in California's Mother Lode country, when Governor Henry Haight called out the state militia to suppress a strike against a wage cut, demonstrated that Vernon Jensen's heritage-of-conflict theme could be applied much earlier in the industrialization of the western mining industry. If Jensen had consulted Myron Angel's History of Nevada, he would have discovered one of the earliest published references to the disruptive Amador War, as well as the role played by the Comstock's union members in organizing the miners at Sutter Creek. Indeed, a former member of the Virginia City Miners' Union, as president and one of the founders of the Amador County Laborers' Association, had called the strike. At the same time, the president of Virginia City's union and a Republican state senator, James Phelan, stumped the California mining country campaigning against Governor Haight, a Democrat, who subsequently lost his re-election bid. Although Lingenfelter was not aware of Governor Nye's call for troops to the Comstock in 1864, a significant oversight, he did present the historical community with a new image of Comstock labor and its fundamental role in the unfolding of the heritage of conflict in western mining. He concluded:

Indeed, the tradition of militant industrial unionism, fostered by the early miners' unions, reached its fullest expression in the Western Federation of Miners, and ultimately sparked the radical socialism of the Industrial Workers of the World. From the first labor agitation on the Comstock, the miners had rejected "pure and simple" trade unionism to embrace industrial unionism. Vowing to "boldly defy ... the tyrannical, oppressive power of Capital," the Comstock unions had lead [sic] the way in organizing all underground miners and demanding a uniform minimum wage for all, regardless of their level of skill. This policy was sharply attacked by trade unionists as well as by the mine owners, but it remained a fundamental principle of the western mining labor movement. 24

Lingenfelter's study, while certainly the most comprehensive treatment of the Comstock miners and their unions, was by no means exhaustive. Two more recent works, Ronald C. Brown's Hard-Rock Miners: The Intermountain West, 1860- 1920 (1979) and Mark Wyman's Hard Rock Epic: Western Miners and the Industrial Revolution, 1860-1910 (1979), have greatly contributed to the body of knowledge regarding the working and social life of the metal miner. Although Wyman and Brown consulted many of the extant records of the Comstock miners' unions, the broad nature of their studies did not lend itself to treating labor organizations in any detail.

Wyman, more than Brown, did devote some attention to the Comstock unions. He noted in his chapter entitled "The Union Impulse" that the first attempts at unionization in the mines of the trans-Mississippi West actually occurred in Central City, Colorado Territory, one month before the founding of the Miners' Protective Association in May 1863. While neither organization survived, the union impulse continued on the Comstock. Citing Lord and Lingenfelter, Wyman explained that the Storey County Miners' League failed because, having achieved its goal of maintaining the four-dollar-per-day minimum wage, "the new organization lacked a reason for unity; and when employers began favoring non-League men in hiring, it began to disintegrate." Like every historian and writer on the subject except Hubert Bancroft, Wyman had not noted the devastating effect upon the Miners' League of Governor Nye's call for troops. On the other hand, Wyman broke some new ground in mentioning how the Comstock unions fared after the bonanza years and through the turn of the century.25

We can now say that the heritage of conflict in the metal-mining industry began with the Comstock as the first large-scale industrial development of mining in the trans-Mississippi American West and western Canada. As a result of the labor conflict and military suppression in 1864, the Comstock miners' search for power in combating corporate capital produced a balance of power between the competing interests, based not so much on mutual respect as on the use of force, coercion, volunteerism, and political activity. Just the same, while the Comstock unions perceived the mining companies as adversaries in industrial relations, they did not reject capitalism as a viable economic system, as the WFM and IWW would have. As the unions discovered, the key to power in an area dominated by one industry- where the work force comprised a sizeable number of the total population-lay in influencing and controlling key elements of local government, especially in the realm of public safety and the court system; in maintaining the community's general support, including that of the business sector, which was dependent upon the miners' income; in influencing legislation affecting their interests by electing miners and other sympathetic persons to the state and national legislatures; and in wresting basic concessions involving wages, working conditions, and union security from the absentee-owned mining corporations. In effectively pursuing this type of action on behalf of their rank and file, the Comstock miners' unions left a legacy of success and not of violence. 26

Guy Louis Rocha is the Nevada State Archivist and a longtime student of Nevada labor history. His writings have discussed not only Comstock Lode unionism but also labor disputes in Goldfield and at the Hoover Dam construction site during the Great Depression. For further reading, obtain The Ignoble Conspiracy: Radicalism on Trial in Nevada by Sally Springmeyer Zanjani and Guy Louis Rocha. The above originally appeared in the Fall, 1996, edition of the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly and has been uploaded with the permission of the author. Copyright © 1996 Guy Louis Rocha.

![]()

![]()

Site produced &

maintained by Deciding Factors

Comments

and suggestions appreciated